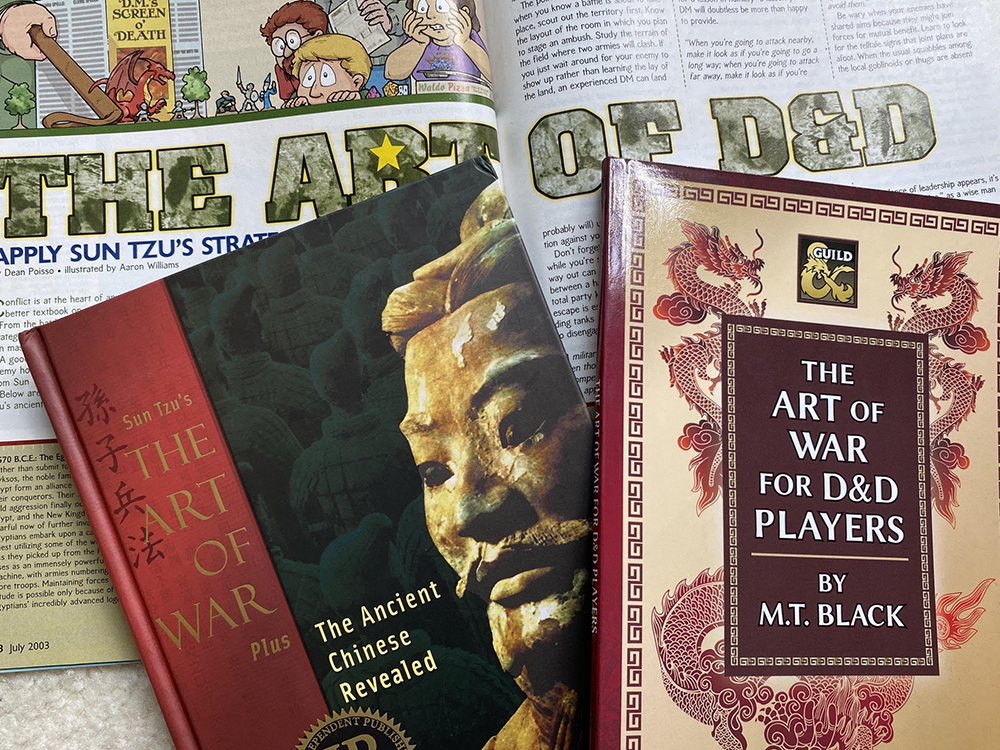

For a book that was written around 2,500 years ago, The Art of War gets a lot of mileage. Most authors would kill for staying power like that even though Stephen King lamented hearing from fans that The Stand was probably his best work. What is it about The Art of War that makes it so ubiquitous? It’s on military leadership reading lists. The business world has coopted the book in the endless drive to increase the bottom line. Then, in 2019, M.T. Black published his take of the treatise by applying the concepts to Dungeons & Dragons. The Art of War for D&D Players is available on DMs Guild in both digital and physical format.

While it may seem like a novel approach to adapt the ancient text to the world’s most popular RPG, Dean Poisso did it seventeen years ago in Dragon #309. I am not suggesting that Black surreptitiously took Poisso’s work and adapted it into his own. Instead, I am emphasizing the aforementioned ubiquity of Sun Tzu regardless of subject or decade. But it is really a treatise with good applicability to the gaming table? Do you need this accessory to increase your odds of survival and success in any given D&D session?

The Art of War for D&D Players

Writer(s): M.T. Black

Publisher: DMs Guild

Cost: $8.95-23.90

Product Length: 69 pages

Available Format(s): PDF and/or Softcover

My copy of The Art of War is the translation by Gary Gagliardi. As a student attending business school a while back, I bought it because I was persuaded that it was an invaluable resource for a budding business scholar. I remember reading it and feeling a bit underwhelmed but I concede now that it could have been my overall disposition of a jaded outlook on business in general. I will use this copy to draw comparisons with what I found in Black’s work even though he used the Lionel Giles translation as his basis. The Giles translation is in the public domain and available from MIT. As near as I can tell, Dean Poisso used the Thomas Cleary translation but he doesn’t explicitly state a particular translation in his 2003 article.

Gagliardi’s translation is broken into 13 chapters:

- Analysis

- Going to War

- Planning an Attack

- Positioning

- Momentum

- Weakness and Strength

- Armed Conflict

- Adaptability

- Armed March

- Field Position

- Types of Terrain

- Attacking with Fire

- Using Spies

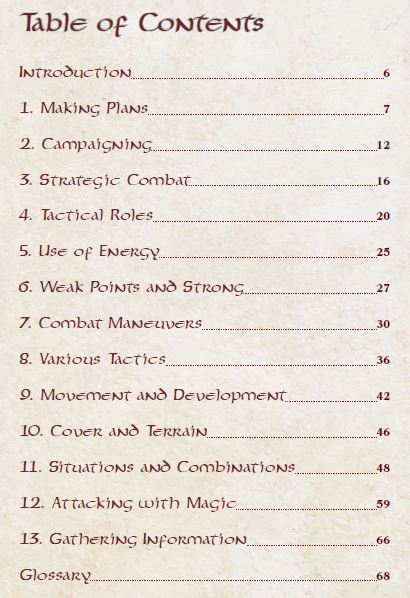

Black also breaks his work out into 13 chapters:

- Making Plans

- Campaigning

- Strategic Combat

- Tactical Roles

- Use of Energy

- Weak Points and Strong

- Combat Maneuvers

- Various Tactics

- Movement and Development

- Cover and Terrain

- Situations and Combinations

- Attacking with Magic

- Gathering Information

But since he only had 6 pages of space, Poisso only covers 6 topics:

- On Assessing Strategies

- On Doing Battle

- On Planning a Siege

- On Force

- On Armed Struggle

- On the Use of Spies

Can Sun Tzu be applied to small-scale D&D combat?

Dragon #309 was the first magazine published after v. 3.5 was released.

It’s accurate to say that Black’s work is a chapter by chapter application against Sun Tzu’s regardless of translation (chapter titles vary across translations but the order of those chapters do not). Poisso’s Dragon article focuses only on chapters 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, and 13. He does not address Positioning, Momentum, Adaptability, Armed March, Field Position, Types of Terrain, or Attacking with Fire. There’s a reason I’m including Poisso in this review that will become evident later.

In the original The Art of War, the author wasn’t thinking of an audience of people who were controlling one (maybe two) people at a time. His intent was to impart military wisdom into individuals who would be controlling armies of warriors. So applying his philosophy on such a small scale is tricky. Both Poisso and Black have done well to scale down the scope to a more granular level and the reader won’t find it hard to apply these tactics to their games. I will only speak briefly about 4 of the chapters that all three works have in common. My thoughts on chapters 1, 2, 3, and 6 follow.

1. Analysis | Making Plans | On Assessing Strategies

In the first chapter, Sun Tzu advises the reader that war is ugly and that a leader can lead troops to death as well as to life. The skillful tactician will learn as much as possible to gain the upper hand and, hopefully, victory. It behooves you to know the philosophy, climate, terrain, leadership, and methods of any given situation.

Black echoes these sentiments by advising that a D&D party research where they’re going and the parties involved. Additionally, he suggests that you stock up on supplies (can you have too many arrows?), power up (if you can afford to silver your swords, you may wanna), and bulk up (hirelings!). Also, do the casters have ideal spells prepared? For example, should the wizard bother with fireball if the party is searching out a red dragon’s lair?

Black also touches on ways of dividing and conquering an enemy whose numbers are superior. The strategies he offers are in accordance with current 5E mechanics and serve as wonderful reminders to players who can otherwise get caught up in a slogging toe-to-toe encounter.

Poisso, writing for a previous edition, does a good job of addressing strategies for success too. Despite the difference between 3.5 and 5, his suggestions are essentially timeless. What it essentially boils down to is this: know your enemy. I’m not suggesting players go read the Monster Manual from cover to cover. But they should definitely use their PCs to gather as much knowledge as possible. You can learn of unlikely allies or weaknesses (as when the thrush told Bard the Bowman of Smaug’s weak point). And we all remember the Old Man from the original Zelda NES game, right?

2. Going to War | Campaigning | On Doing Battle

When Sun Tzu was discussing going to war, he meant total war. Troops numbering in the thousands. As such, this is probably where both Black and Poisso take the biggest departures from their inspiration. Nonetheless, Sun Tzu’s main theme of his second chapter involves resource management so perhaps the departure isn’t so big after all. If you’re out of arrows it doesn’t matter whether you are down from a score of them or from thousands. Zero is zero.

Treading closely to meta-gaming, Black mentions the action economy in his second chapter. Unlike many aspects of meta-gaming, I think a keen understanding of the action economy concept makes for more rewarding play overall. It’s no fun to be a miser and hoard all your gold, ammo, spells, potions, and actions while barely scratching by on all your encounters. It makes the combat pillar of gaming unaligned with the other two. A three-legged stool is stable, regardless of whether the legs are equal length. Nonetheless, the surface of such a stool isn’t level and quickly loses its functionality.

Black asserts “the average fight takes just 3 to 4 rounds” A longer fight depletes resources (even hit points aren’t infinite). He’s channeling Sun Tzu who advocates for short campaigns. Essentially, Black suggests you ask yourself, “will [my action] help inflict more damage on the enemy, and/or reduce the amount of damage you receive?” If you answer no, you are likely wasting your turn.

Poisso sums it up nicely with advice to fight dirty, not to attack if you cannot win, and to scavenge everything. Use the enemy’s resources before your own. Lastly, he tells you to die conveniently. Seriously. Don’t make recovering your body an impossible task for your party. They need your stuff even if they can’t resurrect you.

3. Planning an Attack | Strategic Combat | On Planning a Siege

There are two main takeaways in the third chapter of The Art of War. The first is simple but profound: unity > divisiveness. An army cannot hope to succeed if it fights with itself. “Disorder in an army kills victory.”

The second I touched on earlier: “know yourself and know your enemy.” You have to know your capabilities and your limitations as well as those of your enemy.

But where Sun Tzu is broader in his approach, Black gets much more granular by offering references to the Player’s Handbook. For example, “Good tactical positioning can enable you to destroy a numerically superior force. See ‘Concentration and Dispersal’ in chapter 9.” While he flirts with the line of simply telling his readers to just go read the PHB, he doesn’t actually cross it. Just helpful reminders of where to find useful information in the rules as written.

However, he does imply on page 17 (19 in the PDF) that there is a surprise round in 5E. He writes, “Surprise is a very powerful tool. Mechanically, it gives you a round of unopposed attacks.” There is no surprise round in 5E except in the unlikely event that each member of a party individually gains surprise against each member of an opposing party. Surprise lasts until the surprised creature’s normal turn in initiative order passes. Never a full round. But I don’t want to harp on it too much because I’ve already done so in my article, The Surprise Round Doesn’t Exist in 5E.

As his section title suggests, Poisso focuses more on sieges and attacking cities. He sums it up succinctly with a siege pretty much being a “poor choice of strategy.”

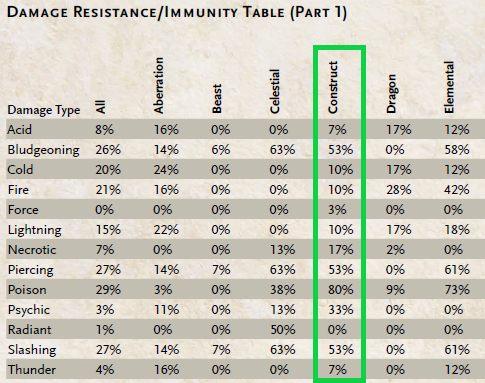

4. Weakness and Strength | Weak Points and Strong | On Force

Weakness and Strength is the sixth chapter of The Art of War. Perhaps more than any other chapter, this one advocates using wits to your advantage. If an enemy cannot pursue you, that’s a good place to withdraw. Find your enemy’s weakness and exploit it. If there is a weak point in their defenses, penetrate there. Draw out your enemy rather than be lured into a trap. Be flexible, adaptive, and powerful. Like water.

This is one of Black’s shortest chapters, at just 3 pages and 1 of those is a table that outlines damage resistance/immunity by creature type. Initially, I found this odd because it’s one of Sun Tzu’s longer chapters. But after rereading it, I realized it’s also one of Sun Tzu’s more repetitive topics. This chapter/section (for all authors) continues to drive the overall philosophy of knowing your enemy.

Poisso offers more timeless tactics such as deceiving your enemy by attacking their warriors first to draw out their cleric, then switching to an all-out assault on the healer and leaving the survivors vulnerable. If the warriors have to spend an action to quaff a healing potion then that’s damage not being dealt against you and your group. He is otherwise fairly circumspect on this topic and fills a lot of his column with Sun Tzu quotes.

Final Thoughts

From a production point of view, M.T. Black’s The Art of War for D&D Players is nearly flawless. My only nitpick aside from the surprise round issue is with the physical book. The print quality is a tad grainy (not that it’s Black’s fault). Another is that the page numbers for the table of contents do not align with the actual page numbers. For example, the table of contents says Chapter 6 begins on page 27 but, it begins on page 25. It’s a small issue, particularly in a book this short. The PDF version is free of both issues.

If you decide you want this product, I don’t suggest the physical book. It’s nice and easy to read. But its smaller size means it won’t work well as a display piece along with your 5E books and I imagine that’s what a collector would want.

I did a search on eBay and found an unopened copy of Dragon #309 (with the included disk) for $14.95. Poisso’s article, The Art of D&D, isn’t as in-depth as Black’s book. Both are worthy of reading and rereading a time or two. But with the magazine, you also get cool articles on speeding up combat, the ecology of hobgoblins, and tips on fighting the githyanki invasion.

Should you buy a copy of The Art of War for D&D Players? Probably. It’s taken the crucial elements of 5E’s combat mechanics and distilled them down into an easy-to-read pamphlet. It doesn’t introduce new mechanics or tweak existing ones. It just shows you how to better employ the rules that are already there. But I contend you buy the PDF and also seek out Dragon #309 to round out your experience.

The post The Art of War for D&D Players—DMs Guild Review appeared first on NZS Games.